Camera: Aryaman Kantawala, Por Tupsamphan

Editing: Por Tupsamphan

Leer este artículo en español

In the Nineteen Seventies, on the streets of the Bronx, hip-hop tradition started to emerge by means of music, poetry, dance, and graffiti. These African American aesthetics have traveled world wide and been adopted by different cultures, as is the case in Bolivia, a rustic greater than 4,000 miles from New York, which has embraced, remodeled, and made hip-hop its personal.

Today, it’s frequent to listen to hip-hop beats blended with the sounds of sikus (pan flutes), quenas, and charangos. Artists additionally fuse the style with Andean kinds reminiscent of huayno, morenada, and caporales, amongst others. Just because it has within the United States, hip-hop has offered Bolivian artists a platform for telling private tales, analyzing sociopolitical points, asserting their very own cultures, and defending the rights of Indigenous peoples. However, this course of has not been straightforward.

According to Eber Quispe, recognized on stage as Eber Miranda, a rapper and member of the Nación Rap collective from El Alto, many individuals in Bolivia didn’t welcome the blending of hip-hop prose and beats with conventional music and devices. Bolivian hip-hoppers like Eber, who pioneered rapping within the Indigenous Andean languages of Quechua and Aymara, have confronted many difficulties resulting from their aesthetic proposals and the social content material of their lyrics.

This mix now comes extra naturally for youthful artists. Among them is Carlos Andrés Orellana Patiño, aka Andes MC, a rapper from La Paz who represents the brand new technology of hip-hop artists on this highland nation. His lyrics give attention to the connection between modernity and ancestry, and the way his technology, by means of hip-hop, creates a hyperlink between the normal and the trendy.

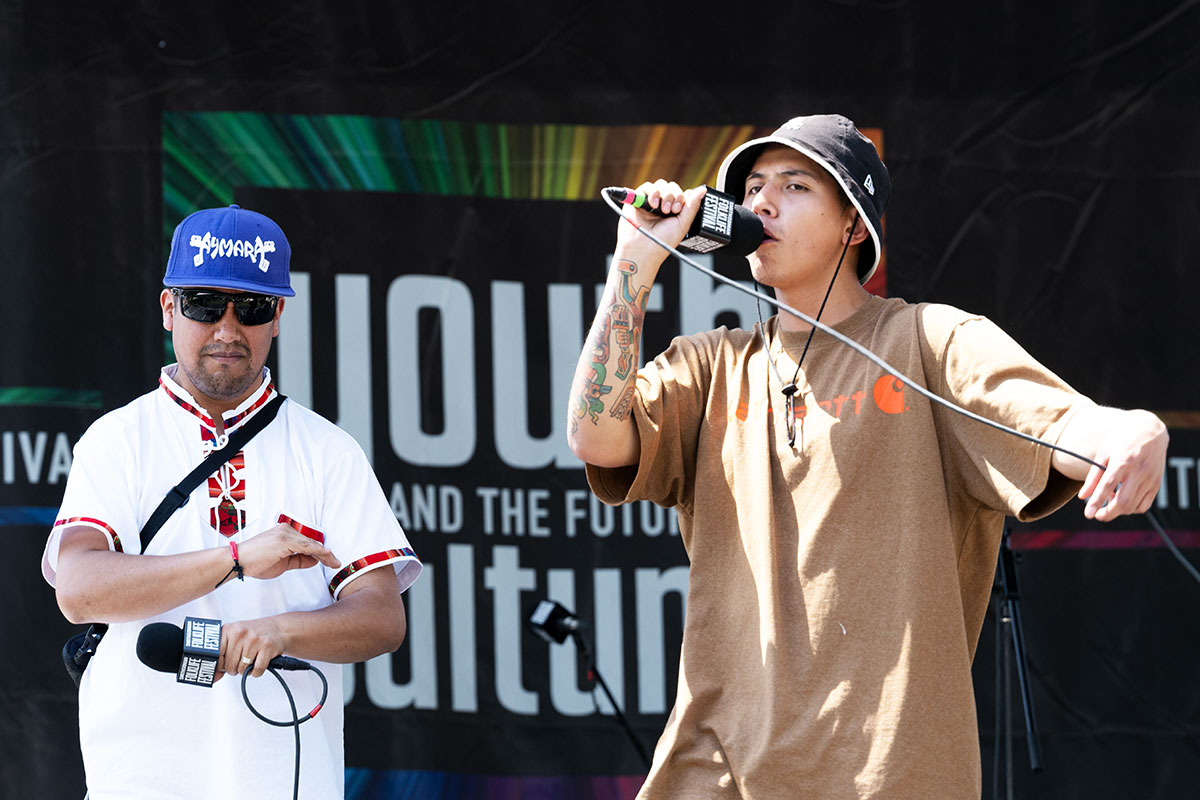

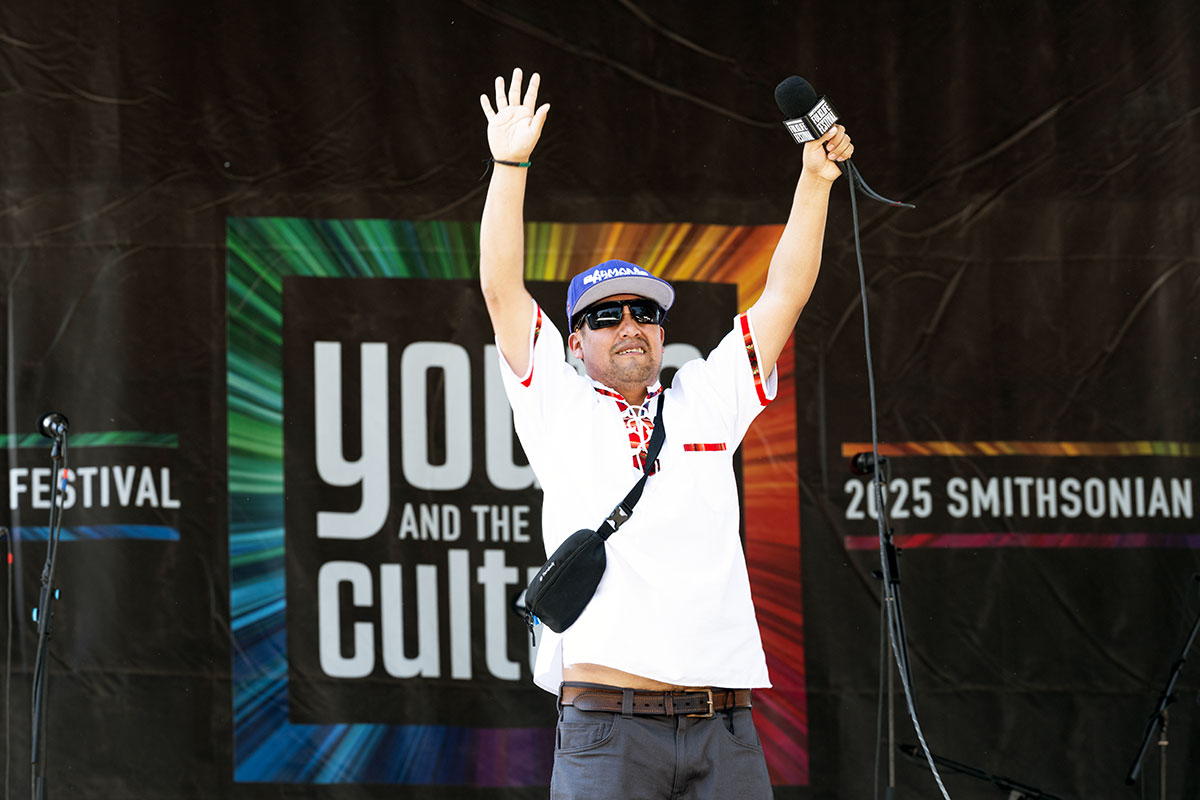

Currently, Eber, age forty, is devoted to passing the torch of Andean Bolivian hip-hop to Andes MC, age twenty-six, his protégé. The two shared their artwork, experiences, and data by means of poetry workshops, concert events, and discussions on the 2025 Smithsonian Folklife Festival, centered on Youth and the Future of Culture, and in an interview after the occasion.

Photo by Ronald Villasante, Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives

How do you strategy this concept of utilizing hip-hop to ascertain a connection between the Andes and African American music?

Eber: I see similarities between the 2 locations, as a result of [in Bolivia] younger individuals are additionally experiencing comparable conflicts. This was a place to begin for me, to inform what is occurring in El Alto and, on the identical time, issues that different younger individuals world wide are additionally experiencing, and the way the response is similar: music, dance, and graffiti.

I additionally began writing to attempt to reclaim my tradition, which has Quechua roots. Before, individuals have been ashamed to say “I am Quechua. I am Aymara.” They have been embarrassed as a result of there have been prohibitions in opposition to talking the Indigenous language. There was additionally disgrace in talking Spanish as a result of we believed we spoke it “badly” or with an accent from the Indigenous language. But you’ll be able to’t disguise your pores and skin, your face. For instance, they used to say to me, “Do you even speak your language?” And I’d jokingly say, “Can’t you see my face?”

There have been vital protests in Bolivia because the Nineteen Seventies, with symbols such because the Wiphala flag, which has now unfold all through Latin America. It is used all through the Andes as a logo of the Indigenous communities there. To unite individuals, we’d like symbols, music, concepts, and languages. Young individuals determine with hip-hop. So, for me, Andean hip-hop—that’s what I name it—is alive.

Why is it very important so that you can be right here at the Festival—not only for you however your Aymara and Quechua communities?

Andes MC: I feel this revitalization of individuals’s language is crucial, as a result of you get to share your tradition. Many individuals ask the place you come from, or the place your tattoos are from. My tattoos symbolize my tradition, a particular place known as Tiahuanaco, and with the ability to present them and speak about them, having individuals present curiosity in them, it offers them worth. They assist different individuals turn into in our tradition, in our individuals, in our territory. This permits us to move on these teachings and what we now have discovered by means of music, as Eber says, like piqchar or venerating the Sun or the Pachamama. All of that offers it worth.

Photo by Shannon Binns, Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives

For our inventive careers, it has been helpful for our music to succeed in a wider viewers, past our nation’s borders. Personally, it was a dream come true to reach right here, within the United States, the birthplace of hip-hop. Since I used to be little, I’ve at all times watched motion pictures, movies, and listened to music. For me, this competition was like residing in a film. In this “movie,” I used to be capable of meet and work together with new cultures, such because the Mohawk and the individuals of Hawai‘i. Being capable of speak about and showcase my tradition by means of my music has been extraordinarily vital to me.

Eber: Sometimes individuals appear to suppose that everybody in Latin America speaks solely Spanish and that we’re all just about the identical. But there are numerous, many alternative cultures all through Latin America. Through the music we now have made, no less than individuals have heard that Bolivia exists, that the Aymara individuals exist, that the Quechua individuals exist, and that there’s a hip-hop motion right here—that we now have our personal methods of understanding the world and our personal music, even when that music originated on the opposite facet of the world, in New York, in Brooklyn, within the Bronx.

What are a few of your favourite reminiscences from the Festival?

Eber: What I keep in mind most is the interactions with the individuals. Even although they don’t perceive the language—Spanish or Quechua or Aymara—they have been guided by the music we made, by the sounds. The most lovely second was being on stage and having individuals hear me, as a result of I felt free. It’s not that I don’t be at liberty every day, however it’s one other type of freedom and expression.

I’m naturally shy. I don’t speak a lot, and I have a tough time talking. On stage, I can specific myself, leap, sing, and transfer round, permitting me to showcase my character totally. For me, that sort of freedom on stage is actually distinctive.

Andes MC: Maybe [one of] the reveals we did on the Wordsmiths’ Cafe. There was a man who began dancing salsa. I known as him over, and he danced all through the total efficiency. I feel that second will stick with me from all of the performances we had that week. The power was excessive, the gang was excited, and they began dancing. I feel that’s a phenomenal second. I actually preferred it as a result of I used to be nearer to the individuals, and you could possibly be head to head.

Tell us in regards to the poetry workshops you led for guests on the Festival.

Andes MC: I discovered the workshops to be rewarding since you notice you turn into like a mentor, guiding them with what you realize, out of your perspective, and sharing your concepts. And you give them instruments in order that they can specific themselves, in search of methods to be impressed, educating them how we are impressed by our place, our nation, our tradition, but in addition to take action from their very own perspective.

Photo by Stanley Turk, Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives

Older individuals got here, youthful individuals, individuals who already knew, individuals who knew nothing. Then seeing them within the presentation exhibiting what they discovered within the workshop, and they noticed that expertise does exist, and seeing how individuals got here and gave their all, paid consideration, and took issues significantly—that area was very, very rewarding for me.

How did you are feeling studying about different cultures and different individuals?

Andes MC: It has been helpful for me as a result of it broadened my thoughts to see different cultures, to learn the way they suppose. Additionally, we will observe similarities, reminiscent of these with the Mohawk contributors. I shared a little bit extra with them, speaking about a few of the phrases they use, additionally in regards to the [sacred] mountains, all that. Being capable of perceive their tradition has been very useful for me, and thru that have, I’ve additionally gained a deeper understanding of my very own. Just as they shared their tales with me, I shared mine with them; it helped me to replicate on what I had discovered and skilled.

Sometimes, while you’re residing your each day life, issues turn into routine, however while you depart your nation, you see it from a totally different perspective.

Eber: Mostly I’ve been listening to [fellow participants’] music and pondering about what I may combine or what concepts come to me after I take heed to them, together with my pals from Hawai‘i who taught with their hands, or my Navajo friends who have their own history, and the others who also made crafts. They’ve given me a number of concepts to discover extra music and perceive different musical genres, and perhaps use these to enrich my very own music sooner or later. So I suppose that’s additionally true to hip-hop, as a result of hip-hop is not one thing, in a method, “pure,” as a result of the vinyl data they sampled, the primary vinyl data, are from varied different genres.

Has the Festival modified your outlook in your profession?

Andes MC: I really feel just like the Festival has marked the starting of one thing, a contemporary begin. I’ve been making music for 5 years now, however the Festival represents a renewal for me. I envision myself making a lot extra music, taking part in different festivals, and releasing extra music. The Festival was additionally a place to begin for one thing new, reminiscent of utilizing extra samples and fusing totally different kinds extra. I’m going to create one thing new, provide you with a brand new sound. Continuing to make music is essential to me.

I’m going to maintain making music, regardless of what, whether or not one individual listens to me or hundreds. Music is one thing that fulfills me. Hip-hop is one thing that may at all times be part of my life. The thought is to broaden the music and let many extra nations know that rap in Bolivia is nice too.

Eloy A. Neira de la Cadena is a curatorial assistant on the Smithsonian Folklife Festival and an ethnomusicology PhD candidate on the University of California, Riverside.

Photo by Brandon Weldon, Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives

En los años 70, en las calles del Bronx, la cultura del hip-hop empezó a crearse a través de estéticas musicales, poéticas, dancísticas y murales. Estas estéticas han viajado por todo el mundo y han sido adoptadas por las culturas locales, como en el caso de Bolivia, un país que está a más de cuatro mil millas de distancia de Nueva York, y que acogió, transformó e hizo suyo también el hip-hop. Hoy en día es muy regular escuchar beats de hip-hop mezclados con los sonidos de los sikus (flautas de pan), las quenas y los charangos; asimismo, este género se fusiona con géneros andinos como el huayno, la morenada y/o caporales, entre otros.

En los Andes bolivianos, desde el año 2011, Eber Miranda (Eber Quispe), rapero de El Alto-Bolivia, y miembro de Nación Rap –colectivo de raperos bolivianos– , fue uno de los pioneros en la mezcla del hip-hop con sonoridades y músicas locales. Y lo más singular es que empezó a rapear en lenguas andinas, como el quechua y el aymara.

A través de la poesía, la métrica, la narrativa y la lírica del hip-hop, al igual que para los afroamericanos en los Estados Unidos, en Bolivia el hip-hop se ha convertido en una plataforma para contar historias personales, así como para comunicar preocupaciones sociopolíticas, reivindicar culturas propias y defender los derechos de los pueblos originarios. Sin embargo, este proceso no fue fácil; Eber nos cuenta, por ejemplo, que en Bolivia muchas personas no veían bien que la prosa y los beats del hip-hop se mezclaran con las músicas o instrumentos tradicionales, y los hip-hopers bolivianos enfrentaron muchas dificultades por sus propuestas estéticas y por el contenido social de sus líricas.

Ahora Eber está dedicado a pasar la antorcha del hip-hop andino-boliviano a la juventud y, junto con su joven discípulo rapero Andes MC (Carlos Andrés Orellana Patiño) de La Paz, compartió sus saberes a través de talleres de creación poética, conciertos y discusiones durante el Festival de Cultura Popular del Smithsonian 2025, titulado Juventud y el Futuro de la Cultura.

Photo by Shannon Binns, Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives

¿Cuéntenos cómo se sintieron en el competition?

Eber: El competition ha sido una experiencia muy interesante para mí, mi carrera y mi vida. He conocido mucha gente que está en el arte, no solamente en la música, y ha sido muy importante ver familias de artistas de muchos lugares de Estados Unidos y del mundo.

¿Cuál fue el momento más bonito? ¿Cuál es uno de esos recuerdos que te llevas del competition?

Eber: Lo que más recuerdo es el contacto con la gente, que aunque no entiende el idioma, el castellano, o el quechua o aimara de Sudamérica, pero la gente se ha guiado por la música que hemos hecho con Andes MC, más por los sonidos. Y el momento más bonito ha sido estar en el escenario, que la gente pueda escucharme, porque yo me siento libre en el escenario, no es que no me sienta libre viviendo cada día, pero es otra forma de libertad, y expresarme y que haya ese contacto con las personas, es el momento más especial para mí.

Yo no hablo mucho con las personas, y diría que de personalidad soy tímido, no hablo mucho y me cuesta hablar. En el escenario ya puedo expresarme, saltar, cantar, moverme de aquí para allá, entonces así puedo mostrar mi whole personalidad; para mí esa forma de libertad en el escenario es única.

¿Y qué sentiste a la hora de cantar en quechua, en aymara, en el competition?

Eber: Yo no imaginaba que iba a ir a un competition tan grande como el Smithsonian Folk Festival. Como te decía, la música tiene sonidos, la palabra tiene sonidos, entonces sencillamente puedes utilizar tu idioma para otras formas de expresión y el idioma sigue existiendo a través de los sonidos, sigue viviendo, sigue vigente. [En Bolivia] me decían, “¿cómo vas a mezclar lo autóctono con el hip-hop, el hip-hop es de Estados Unidos, vos no eres de Estados Unidos”; a veces recibía críticas cuando period muy joven o críticas bastante duras en Internet, en YouTube, hasta ofensivas, pero a mí no me importaba, porque hago lo que me gusta y lo hago con mucho corazón, con mucha pasión. No hablo de cosas violentas, no hablo de cosas sin sentido, simplemente estoy expresando poesía en quechua, poesía en aymara, y la mezclo con instrumentos andinos. Ha sido un proceso de aprendizaje también para mí y ha sido algo bien sorpresivo que he logrado llegar acá y también poder haber venido con Andes MC para que él también pueda mostrar sus formas de entender la música.

Photo by Ronald Villasante, Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives

¿Cómo se sintieron aprendiendo de otras culturas, de otra gente? ¿Qué se acuerdan del intercambio cultural?

Andes MC: Para mí ha sido de mucha ayuda porque me expandió la mente ver otras culturas, saber cómo piensan. También ver las similitudes que tenemos, como con los Mohawk; yo compartí un poco más con ellos, hablando de algunos términos que usan y hablan también de las montañas [sagradas], todo eso. Para mí ha sido de mucha ayuda poder entender su cultura y, desde esa experiencia, también entender la mía, porque al igual que ellos me contaban, yo les contaba de lo mío; yo iba refrescando lo que aprendía, lo que vivía. Como que a veces viviendo el día a día se te vuelve muy cotidiano, pero cuando gross sales de tu país, ya lo ves con otros ojos.

Eber: ¿Qué he aprendido? He visto varios artistas. Entonces, más que todo he estado escuchando su música y aprendiendo qué podría mezclar o qué thought me viene al escucharles, incluso a los amigos de Hawái que enseñaban con las manos, o los amigos Navajo que tienen su propia historia y los otros que hacían artesanías también. Entonces me han dado varias concepts de explorar más música y entender otros géneros musicales y para tal vez en el futuro complementar mi música. Entonces yo creo que eso es también el hip-hop, porque el hip-hop no es algo, entre comillas, “puro”, porque los vinilos que se mezclaron, los primeros vinilos, son de otros y otros y otros géneros.

¿Esta thought de usar el hip-hop y establecer una conexión entre los Andes y la música afroamericana, tú cómo la encuentras, cómo la estudias?

Eber: […] yo veo similitudes entre los dos espacios, porque allá [Bolivia] también los jóvenes están pasando conflictos similares. Esto fue un punto de partida para mí, para contar [a través del hip-hop] lo que está sucediendo en El Alto [mi pueblo], y a su vez, cosas que están viviendo también otros jóvenes alrededor del mundo, y como la respuesta es la misma, la música, el baile, el grafiti. Yo empecé a escribir también tratando de reivindicar mi cultura, que tiene raíces quechuas. Antes la gente se avergonzaba de decir “yo soy quechua, yo soy aimara”, se avergonzaba porque había prohibiciones para hablar el idioma autóctono. También la vergüenza al hablar castellano porque creemos que lo “mal” o con un acento del idioma autóctono o del idioma nativo. Uno no puede esconder su piel, su rostro; por decir, a mí me decían, ¿tú acaso hablas tu idioma? Y yo en broma les decía, ¿acaso no ves mi cara? Entonces, han ocurrido reivindicaciones muy grandes en Bolivia desde los años 70 con símbolos como la wifala, que ahora se ha extendido por toda Latinoamérica, en todos los Andes ya se usa y claro es un símbolo de los pueblos. Para unir personas necesitamos símbolos, necesitamos música, necesitamos concepts, necesitamos idioma, y a los jóvenes les identifican con el hip-hop. Entonces, para mí el hip-hop andino, yo lo denomino así, está vivo

Photo by Shannon Binns, Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives

¿Y en términos no solo personales sino para tu comunidad, y Eber estoy pensando en la gente de El Alto, pero también estoy pensando en las comunidades aimaras y quechuas, por qué es importante que ustedes estén ahí, que ustedes estén viajando?

Andes MC: Yo creo que es muy importante esta revalorización del idioma de la gente, porque tú vas mostrando, porque mucha gente pregunta de dónde vienes, de dónde eres o de dónde son tus tatuajes y es como que para mí ha sido como un canal hablar de mis tatuajes, porque mis tatuajes representan mi cultura, a un sitio específico que es Tiahuanaco, y poder mostrarles y hablarles y que la gente se interese, como que le dé este valor, para que otra gente se interese en nuestra propia cultura, en nuestra propia gente, en nuestro propio territorio en el que estamos, y así poder dar estas enseñanzas o lo que nosotros hemos aprendido a través de la música, como cube Eber, piqchar o venerar al Sol o a la Pachamama, todo eso es como que le da un valor.

Eber: Bueno, hay muchos jóvenes que te ven, igual a Andrés, y se inspiran de alguna manera. Inspiras y dicen: “yo también puedo hacerlo”, o sea, se sienten orgullosos, incluso la familia de la que tú has salido, cómo lo has logrado; o alguien que te decía: “¿para qué haces música?”. Pero, al closing, te das cuenta de que se puede, a veces la vida te da sorpresas, y la música y el arte te pueden abrir algunas puertas, pero no es rápido. Yo recuerdo la primera vez que fui a cantar, solo me dieron un sánguche, pero yo seguía y seguía y no lo hacía por el dinero.

¿Y por qué les pareció importante estar en el Festival?

Andes MC: Para nuestras carreras artísticas ha sido de mucha ayuda poder llegar, que nuestra música pueda llegar, que salga del país. Y en lo private fue como un sueño ir hasta allá, hasta Estados Unidos, el lugar de origen del hip-hop. Desde pequeño siempre veía películas, movies, música. Para mí este competition fue como vivir una película. En esta “película” he podido conocer y convivir con nuevas culturas, por ejemplo, los Mohawks, las personas de Hawái. Poder hablar y mostrar sobre mi cultura a través de mi música ha sido sumamente importante para mí.

¿Qué les gustaría ver en un futuro competition?

Eber: Más rap, que siempre haya un espacio para el hip-hop, ya sea grafiti, ya sea DJ, break, que haya siempre algo del hip-hop. Esperamos que haya un espacio para invitados de afuera y que siga siendo una oportunidad para otras personas, como una forma de dar a conocer su música. Al closing uno siempre quiere que esté su gente…

Photo by Ronald Villasante, Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives

¿Qué cosa última quisieran decir para cerrar?

Andes MC: Yo quiero hablar de cómo veo más adelante mi carrera. Siento que el Festival ha sido el comienzo de algo, de otra cosa nueva. Yo vengo haciendo música ya desde hace cinco años, pero pienso que el Festival significa una renovación para mí. Me veo haciendo mucha más música, participando en otros festivales, sacando más música. También el Festival fue un punto para comenzar otra nueva cosa, como usar más samples, fusionar más esta música, voy a hacer algo nuevo, sacar un sonido nuevo, y seguir haciendo música, es algo muy importante para mí. Como cube Eber, igual yo voy a seguir haciendo música, pase lo que pase, me escuche una persona o me escuchen miles. La música es algo que me llena, el hip-hop es algo que siempre va a estar presente en mi vida. La thought igual es como que expandir la música y poder dar a conocer a muchos más países que el rap en Bolivia es bueno también.

Eber: Como palabras finales… A veces hay personas que parece que piensan que en Latinoamérica solo se habla castellano y que todos somos casi iguales, pero hay muchas, muchas culturas dentro de toda Latinoamérica, y mediante la música que hemos hecho con Andes MC por lo menos han escuchado que existen, que existe Bolivia, que existen aymaras, que existen quechuas y que existe un movimiento hip-hop; es decir, que existimos y que tenemos nuestras propias formas de entender el mundo y nuestra propia música, aunque haya nacido en otro lado del mundo, en Nueva York, en Brooklyn, Bronx. Mil gracias, mil gracias.

Eloy A. Neira de la Cadena es asistente curatorial en el Smithsonian Folklife Festival y candidato a doctorado en etnomusicología en la Universidad de California, Riverside.

Source link

#Andean #HipHop #National #Mall #Andes #Eber #Miranda