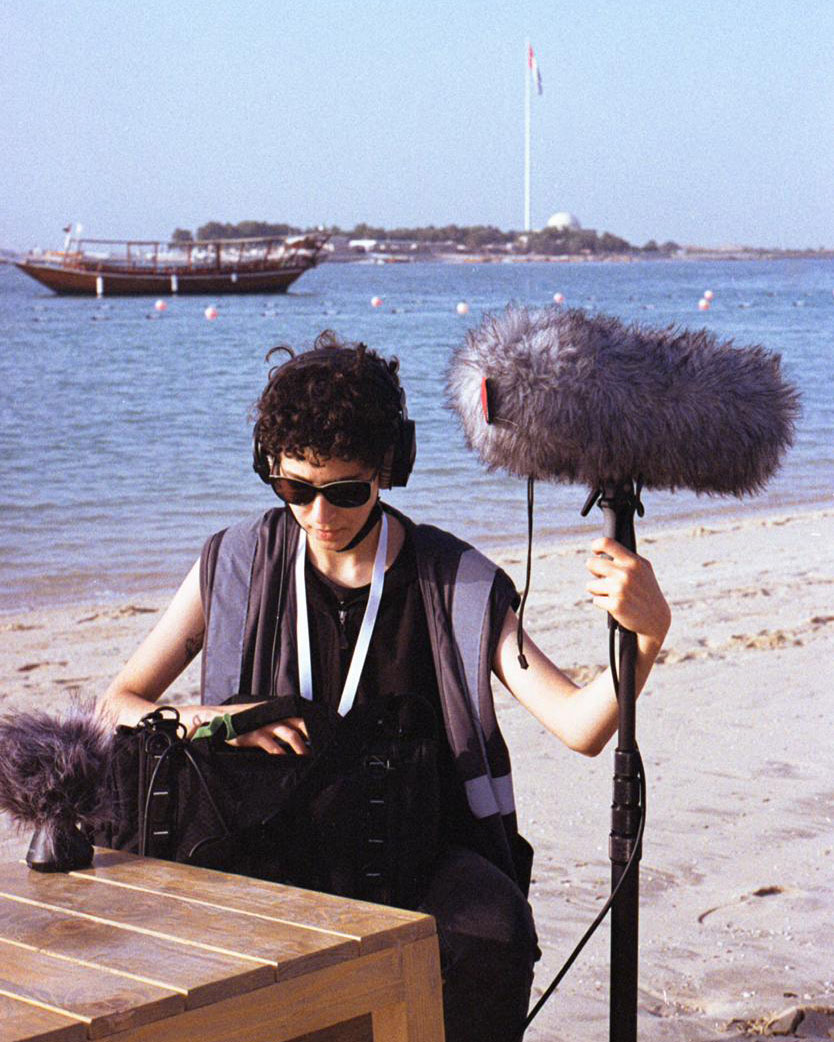

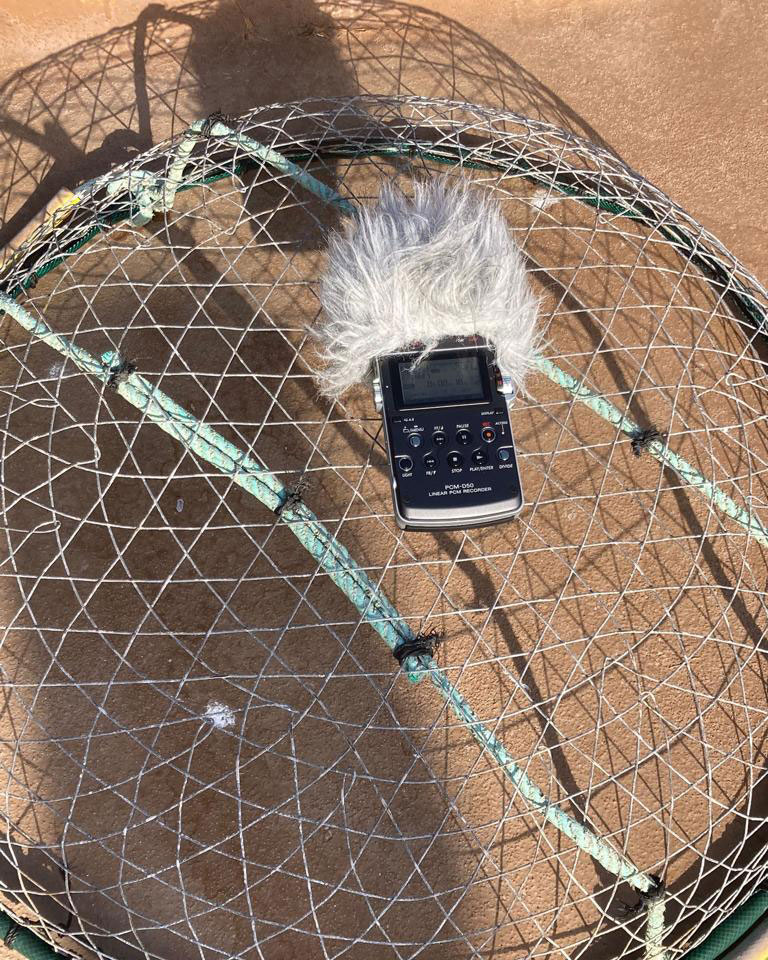

For the Festival’s soundscape set up, Diana Chester recorded sounds and voices of the United Arab Emirates, together with these of camels.

Photo courtesy of Diana Chester

At the Folklife Festival, many guests have been drawn to a curious, curved set of benches below the bushes, anticipating a short respite from the solar. They discovered themselves submerged in a sonic surroundings that took them far-off from Washington, D.C.’s National Mall, as outside audio system, inconspicuously connected to wood beams above, showered them with sounds from the United Arab Emirates. One viewers member admitted, “I didn’t know what I ran into, but I sat there and enjoyed it for a long time.”

This is the primary authentic sound set up created for the Smithsonian Folklife Festival.

The set up, Living Landscapes, Living Memories, is a soundscape created by artist Diana Chester and her workforce—Safeya Al Blooshi, Mohamed Al Jneibi, Mansour Al Heera, and different college students from NYU Abu Dhabi—to current the sounds of the UAE. While there may be ongoing debate on the definition of the phrase “soundscape,” the time period, typically seen as popularized by R. Murray Schafer, describes the totality of an acoustic surroundings. Like a panorama, it comprises pure and cultural, improvised and composed components.

The set up’s title, in tune with the Festival’s UAE program theme, signifies the workforce’s two concentrations. Living Landscapes consists of area recordings from completely different geographical places within the UAE, together with Mina Port, Dubai Creek, Al Ain Oasis, Liwa Desert, Saadiyat Island, Khor Kwair Village, and lots of extra. Living Memories is a mixture of interviews.

“I would ask people to tell me a story about something in their life that relates to the UAE or record them telling me a memory of one of their favorite things in the country,” Chester defined. After greater than 100 interviews, accomplished with the help of workforce members, she melded the sounds into eight one-hour loops.

By meticulously arranging the audio system, every projecting sound in a distinct course, Chester created a wealthy, multidimensional, sonic surroundings. The spatialized audio is so deep with cultural and environmental inferences that it creates a misleading impact. When chanting was performed by the audio system, curious audiences spun their heads round searching for stay musicians; when sounds of seagulls on the fish market cycled by, guests instinctively ducked.

Photo by Ronald Villasante, Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives

Photo courtesy of Diana Chester

Photo courtesy of Diana Chester

Chester, at present a school member on the University of Sydney, has lived within the UAE for greater than six years. She refers to herself as an ethnographer who makes use of sound as a medium to specific cultural and non secular traditions. Much of Chester’s work focuses on Islamic tradition, however her motivation is multifaceted.

“There’s a personal bend, a political bend, and a creative bend,” she stated.

Although Chester was raised Jewish, she found later in life her household’s Islamic heritage.

“My father’s family is part of an ethnic minority group that emigrated from Mongolia in the 1300s to Eastern Europe, and then to the United States in the 1800s. He married outside of the community. But I would have been raised Muslim if I were to be born a generation earlier.”

Chester was nineteen when 9/11 occurred. Since then, she has seen societies develop more and more Islamophobic. She hopes to give you her personal methods to problem biases.

After transferring to the UAE for work, she turned enamored by adhan, the Muslim name to prayer that’s broadcast 5 occasions a day. The sound resonates in each nook of the town, from the mosques to the streets. “It has become a huge part of my daily sonic experience,” she stated. Chester began creating sound artwork based mostly on adhan, together with a number of installations targeted on sensor-based interactivity.

But why sound?

“A photographer uses their camera as a way of seeing the world,” Chester replied enthusiastically. “The audio recorder is my tool for hearing and understanding the world.”

According to research, people are visible creatures who rely extra on eyesight than listening to. “We can get a glimpse of something and make swift judgments and decisions,” Chester stated. But whereas sound is omnipresent, and nearly inconceivable for most individuals to disregard utterly, the ears of most stay numb, untrained.

Chester provided a enjoyable pedagogical train: “I ask the students to observe a space for a few minutes. Most of them can’t recall what the space sounded like, but they can describe vividly what it looked like.”

Photo courtesy of Diana Chester

Photo courtesy of Diana Chester

Photo courtesy of Diana Chester

One workforce member, Al Blooshi, a current graduate of music from NYU Abu Dhabi, is fascinated by the ever-present high quality of sound. “Sound is something that transcends what we hear,” she stated. “Sounds are essentially vibrations that pass through us and bounce off surfaces, and even if we can’t hear them, they are still present. Other living things might be affected by them, whether they are animals or plants.” For Al Blooshi, sound is a cross-sensory expertise. “The visual, we see through the eyes, but sounds—that’s something we can feel.”

Opening up our auditory senses brings new potentialities of expertise.

“Many images regarding Muslim culture—” Chester began, pausing for the suitable phrase to return, “are weaponized to some extent.” Certain visible characters seem repeatedly, lowering people to mere symbols and conveying an usually unsubstantiated, unilateral illustration of a gaggle. Careful listening can break down these stereotypes.

Living Memories captured the range of identities within the UAE, encompassing many languages, together with Urdu, Arabic, Levantine Arabic, English, Hindi, and extra. Chester curated and categorized the interviews based mostly on the subjects that emerged, however every voice represents a distinct perspective. “There’s a section where an Emirati man, an Indian woman, and a Sri Lankan woman spoke about female prayer spaces, and they have really different experiences.”

There are additionally tales which can be common and evoke empathy. Among the interviewees, one lady, initially from Jordan, who spent thirty years residing within the UAE, recalled her intense longing for McDonald’s. When she was pregnant and residing in Abu Dhabi, the nation’s first McDonald’s opened in Dubai, and he or she determined to journey there with out hesitation. At that point, the street between Abu Dhabi and Dubai, which is now a freeway, was a tiny street with velocity bumps and camel crossings. It was a tough journey, longer than anticipated, however she remembered the meals to be great.

“It was a random but very relatable and universal story,” Chester stated. “There’s nothing in it to do with being in the UAE, being of a certain religion, or speaking a certain language. It just has to do with being pregnant and craving a certain food, which fifty percent of the population can relate to.”

Because the workforce selected to current a number of views inside the soundscape, they revealed a universality relatable to audiences throughout cultures. “The purpose of juxtaposing contrasts and commonalities is so people bring their own imaginations and expectations, and then hear something completely different,” Chester defined. “Several voices blend and blow open what you might have previously assumed.”

Photo courtesy of Diana Chester

Photo courtesy of Diana Chester

Photo courtesy of Diana Chester

Beyond capturing sound from varied websites within the UAE, from city to rural and ocean to abandon, Living Landscapes additionally serves as an archive and a gateway to the previous. Al Jneibi, an city planner and architect, instructed the Festival viewers that the set up additionally included sounds from locations which have disappeared.

“I learned more about my country as I was recording and listening to the people and landscapes,” he added. In Abu Dhabi, they recorded contained in the Assiri Mosque. “That was precious, since it was rare to find Indian-style mosques.” The mosque has been changed by a visitors circle. However, the echoes of long-gone chants are preserved in audio recordings. As landscapes endure fixed renovations, sound recordings act like time capsules.

Another workforce member, Mansour Al Heera, a filmmaker and archivist, recorded sounds of his family and his mother cooking meals. Both the marvelous and the mundane are captured within the soundscape, presenting the range of Emirati lives.

To create a soundscape isn’t merely a matter of recording. Sound artists, by their picks, preparations, and designs, are the medium between disordered sounds and a synthesized entire. Al Blooshi shared one of her favourite experiences, planning a story of the Hindu neighborhood in Dubai. She referred to the method as a soundwalk, one other time period and idea traced again to R. Murray Schafer and composer Hildegard Westerkamp.

“I walked through the old Dubai town, from the streets to the temple,” Al Blooshi described. The uncooked recordings have been messy. The artist needed to choose essentially the most consultant components and organize them into one thing that captured the neighborhood’s spirit, together with languages and music. “It is through me walking through the city that I allow the audience to listen to the community.”

During the Festival, Chester additionally held a workshop, instructing guests the strategies of recording their very own soundscape. “To develop your ability to listen carefully, the first step is to learn how to record,” she instructed the viewers. During the session, Chester launched “deep listening,” a way first coined by the groundbreaking composer Pauline Oliveros to “heighten and expand consciousness of sound in as many dimensions of awareness and attentional dynamics as humanly possible.”

After a number of meditation practices, workshop individuals expressed that they’ve begun to note a distinction. Their ears turned extra acute to micro-movements; they have been extra targeted on human voices; sounds turned extra spatialized of their heads.

“One of the unique things about sound is that there’s so much about selectivity in what we hear and how we perceive sounds through a cultural lens,” Al Blooshi defined. “But on the other hand, perceiving sound is also in our basic human instinct.”

For Chester, listening, from a cultural and sensory standpoint, is essential to understanding individuals and our located areas. “A big part of the soundscape is about challenging people’s thinking and breaking down the barriers of misunderstanding.”

Instead of preaching, the workforce offers a sensory different, utilizing sound to convey the residing tradition of the Emirates to the National Mall for all to really feel.

Yuer Liu is a writing intern on the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, an aspiring anthropologist, a conventional Asian puppetry performer, and an undergraduate at Stanford University. Her analysis pursuits embody materials tradition, sound artwork, and multi-species ethnography.

Source link

#Soundscapes #UAE #Sound #Challenges #Stereotypes